[ad_1]

ExplainSpeaking-Economy is a weekly newsletter by Udit Misra, delivered in your inbox every Monday morning. Click here to subscribe

Dear Readers,

This is going to be a crucial week for the Indian economy.

To begin with, even before the Union Budget is presented on Wednesday, the immediate future of India’s stock markets and the well-being of retail investors is likely to be determined by how the stocks of Adani Group of companies perform on Monday and Tuesday. Already in 2023, even without the allegations and findings by Hindenburg Research, the Indian stock markets were one of the worst-performing ones anywhere in the world. In particular, foreign investors have been pulling out money from India. The Adani Group, which has already lost billions of dollars in market value in a matter of few days, has issued a detailed rebuttal but it all depends on how investors view it.

Then on January 31st, two key documents will be released.

One, is the Economic Survey, prepared by the Chief Economic Advisor. Two, Tuesday will also witness the release of the International Monetary Fund’s latest update of its World Economic Outlook. Both documents will carry pointers about the prospects of India’s economy.

On February 1, the US central bank will also release its next policy decision. The US Federal Reserve’s decision will likely have a bearing on Indian markets as well as the RBI’s own monetary policy stance, which is due to be revised later on in February.

But perhaps the most far-reaching impact will be that of the Union Budget. As explained in one of the previous editions of ExplainSpeaking, 2023 is expected to be a particularly challenging year from the perspective of economic growth because base effects will wear off and India’s true economic momentum is likely to be revealed. The outlook of muted global growth, if not an outright recession, further makes the year tough. A sustained high-interest rate regime in the US will put pressure on Indian policymakers to keep interest rates high at a time when they may want to bother more about growth, given that the domestic inflation trend is starting to ease a bit.

Lastly, there is continued geopolitical uncertainty. Not only has the Ukraine conflict not been resolved but there are early signs of growing tensions between the US and China. Reuters quoted a top Republican in the US Congress on Sunday that the odds of conflict with China over Taiwan “are very high”.

The significance of all these factors is further exalted by the fact that India is getting into a heavy political season with several state elections in 2023 and the national general election in early 2024.

While several of these factors — such as what happens in the rest of the world economy, the US Fed’s decision, the geopolitical uncertainty, and the way stock markets react — may be outside the government’s control, the Union Budget can play a big role in steadying the ship.

But how can one evaluate or judge a Union Budget?

It is true that Union Budgets tend to differ from one year to another. However, here are five metrics on which any Union Budget must come through.

1: The Budget speech: Often more is less

Abraham Lincoln once apologised for writing a very long letter. But the reason he gave for doing so was quite instructive.

“I’m sorry I wrote such a long letter. I did not have the time to write a short one,” wrote Lincoln.

Another legendary US president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (or FDR) advised: “Be sincere, be brief, be seated.”

The speech introduces the Budget to the public. Shorn of all the chatter around it, the Budget is essentially an annual financial statement. What the public needs to know is whether they will be taxed more or less, whether the government will be able to make its ends meet (and if not, then how much will it borrow from the market) and, lastly, where will the government spend all its money.

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has already delivered the longest Budget speech in India’s history. But more often than not, a long speech suggests either too much tinkering or a lack of clear focus.

For instance, in his very first speech in 2014, then FM, late Arun Jaitley, announced close to 27 new schemes with an allocation of Rs 100 crore each. These schemes ranged from the modernization of madrasas to a program promoting “good governance” and from a national mission on Pilgrimage Rejuvenation and Spiritual Augmentation Drive (PRASAD) to transforming existing employment exchanges into career centres etc.

While Rs 100 crore may appear a big enough amount for a common person, in the overall scheme of things (the Union Budget that year was of almost Rs 18 lakh crore), this is a minor amount, and the move to start so many schemes with such a meagre allocation is aimed more at scoring political points or blunting criticism than actually achieving a clear policy goal.

Similarly, one can recall railway ministers of the past painstakingly announcing the name of each and every new train that they were commissioning on the eve of a general election.

2: The Budget numbers: Credibility is the key

As explained in last week’s piece, the whole Budget is based on certain assumptions of economic growth and revenue buoyancy. But sometimes the government’s assumptions leave everyone puzzled.

For instance, in the full Budget for 2019-20 — the first Budget of the second government under Prime Minister Modi — FM Sitharaman assumed a nominal GDP growth of 12%. Assuming inflation to be at 4%, which is the RBI’s mandate, this suggested that the FM expected the real GDP to grow by 8% in 2019-20.

“GDP for BE 2019-2020 has been projected at Rs 21100607 crore assuming 12.0 % growth over the estimated GDP of Rs 18840731 crore for 2018-2019 (RE),” stated the Budget at a glance document. BE refers to Budget Estimate and RE refers to Revised Estimate.

There was only one problem. This Budget was presented in July and by then it was clear to all observers that India’s economy was slowing down quite sharply. In fact, soon enough the government’s own data revealed that the economy grew by just 5% in the first quarter of that financial year (April to June). What’s more, the economy had been facing secular deceleration since the start of 2017-18.

As it happened, the economy grew by just 3.7% that financial year — less than half of what the FM had envisaged more than a quarter into the financial year.

This meant that all other Budget calculations were upset. But equally importantly, it undermined the credibility of the Budget numbers since everyone outside the government doubted the assumption that the economy would grow at 8%.

3: Revenue deficit matters just as much as the fiscal deficit

Fiscal Deficit (read the amount of money the government borrows from the markets) is often the most talked about metric in any Union Budget. That’s for two reasons.

One, India has a legislation — the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act — that stipulates the maximum level of fiscal deficit allowed to any government — Union or state.

Two, if a government exceeds the fiscal deficit it risks the wrath of the markets. A good recent example is what happened in the UK under the leadership of Prime Minister Liz Truss and her chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng. They presented a “mini-Budget” that, in a bid to boost growth, resulted in creating a massive fiscal gap. They had hoped the markets would trust their growth plan and oblige by lending them the money. Instead, the markets snubbed them, leading to a financial crisis that cost both of them their jobs.

In India’s case, however, it isn’t just the fiscal deficit that one should look at. It is equally important to notice the revenue deficit.

Simply put, the revenue deficit is the gap between the government’s everyday expenses (say salaries and pensions) and everyday earnings (taxes, cesses etc).

The original mandate of the FRBM Act was two-fold: revenue deficit of 0% (of GDP) and fiscal deficit of 3% (of GDP).

In other words, fiscal prudence demands that the government meets its everyday expenses by its everyday revenues while borrowing (fiscal deficit) only for capital expenditure (that is, expenditure that is made towards making productive assets such as roads and bridges).

The salient point to understand here is that when the government spends Rs 100 on capital expenditure the returns to the economy are close to Rs 250 while when it spends Rs 100 on revenue matters, the returns to the economy are just about Rs 100.

In other words, by forcing the government to borrow only for capital expenditure, the original FRBM Act helped boost economic growth.

However, in 2018, the government gave up on the revenue deficit condition and now focuses only on fiscal deficit. In the absence of this condition, one can imagine a scenario where the fiscal deficit is 3% (of GDP) but all this money is being borrowed to meet the government’s daily expenses because even the revenue deficit is 3% (of GDP).

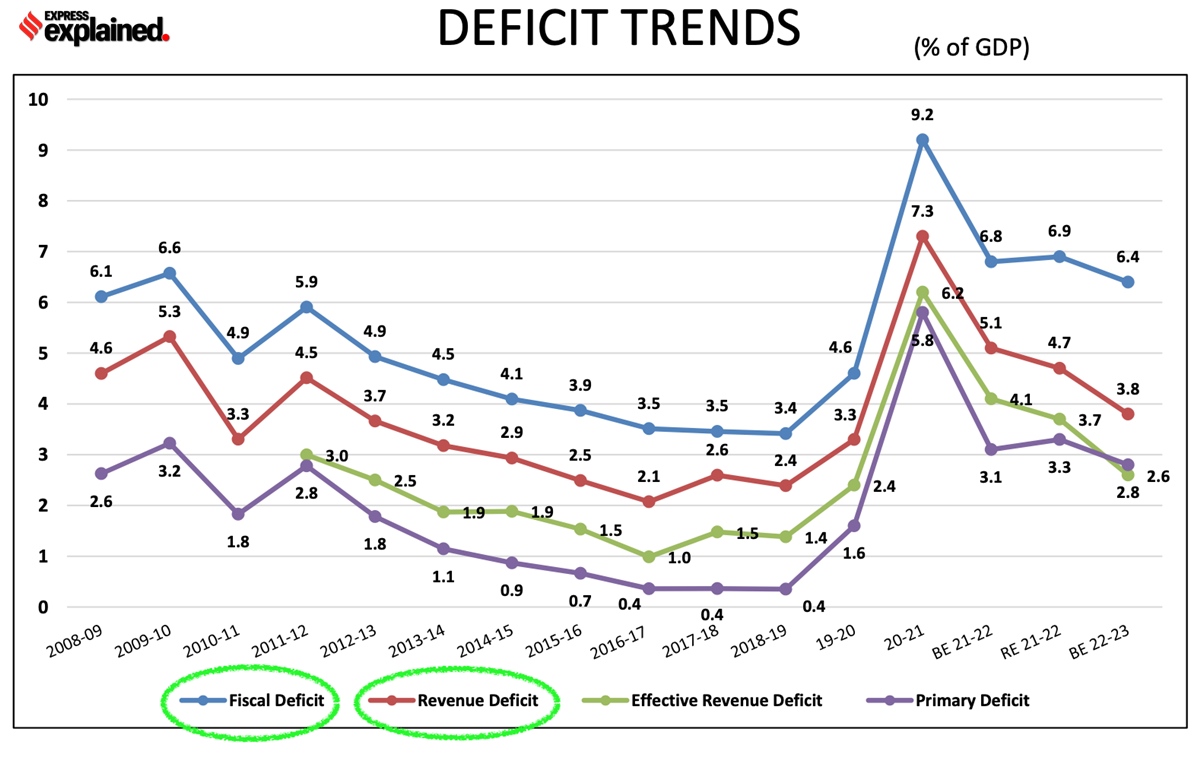

The CHART below, sourced from last year’s Budget, shows how the trend in revenue deficit has worsened since then.

Deficit trends from 2008-09 to BE 2022-23.

Deficit trends from 2008-09 to BE 2022-23.

When the latest Budget is presented, the fiscal deficit figure should be read in conjunction with the revenue deficit data to understand how much of money that the government intends to borrow in the coming financial year will be used towards paying everyday bills and how much of it will go towards boosting the productive capacity of the economy.

4: Revenue targets: Are they realistic and fair?

There are two aspects here.

One, is the calculation of disinvestment targets. A cursory look at past targets over the decades will suggest that disinvestment targets fluctuate quite wildly from one year to another. Often, their achievements also fluctuate just as wildly.

A particular problem is that often the disinvestment target is calculated at the very end of government’s revenue calculations — that is, after revenue assumptions from all other sources are already made. As such, there is a great temptation to stretch the disinvestment target depending on the gap that needs to be filled.

This practice often leads to unrealistic disinvestment targets. This, in turn, undermines the credibility of Budget numbers. That’s because if the disinvestment target is not met in a particular year, it immediately means the fiscal deficit will expand from the budgeted level.

Secondly, when it comes to taxation, there is the question of fairness. Ideally, India should have a tax regime where the taxation rises as one goes from poor to rich. As such, direct tax rates — be it personal income tax or corporate taxation — should rise as one considers richer entities. In the same light, indirect taxation (read GST) should be low because it affects the general population at the same rate and, logically, the poor get hurt the most by higher GST rates.

Of course, GST is out of the Union Budget’s purview. But ideally the government should work towards a tax system with low indirect taxes and progressively high direct taxes.

Given the high inflation over the past few years, it is tempting to argue that the salaried class should get an exemption or some relief — and perhaps they should — but one must remember that the best relief will be in the form of lower indirect taxes. It is by lowering the GST that India’s depressed levels of consumption will improve. Higher demand will also create more economic activity and jobs.

5: Expenditure: What are India’s top priorities?

In allocating expenditure, the trick lies in figuring out the country’s priorities. Pakistan provides a stark example of a nation that prioritised its military power over the health and education of its population.

In India, out of every Rs 100 that the government spends, only Rs 2 goes towards public health. On education, too, the government spends Rs 2.

It spends Rs 10 on defence. Rs 12 is spent on subsidies (food, fuel and fertilisers). And Rs 22 is spent on paying back the interest on past loans.

The expenditure on health is alarming considering that India not only has the largest pool of poor people in the world but also the largest pool of malnourished children in the world.

The same holds for the budget allocation on education. Notwithstanding, rising enrolment in schools, India’s learning outcomes are shoddy.

No country has risen to dominate the world without first substantially investing in the health and education of its people.

All the hopes of India becoming a superpower are contingent on India leveraging its human resources. But while much is made of the promise of India becoming the back office of the world, little is thought of the threat of automation.

There are no easy answers here.

For instance, what would happen if subsidies for fuel and fertiliser are done away with, and the money is shifted towards health and education? The prices of several items — such as foodgrains and energy prices — will go up. One can argue that this should be done. A portion of the ensuing savings can be given directly to the people who are too poor to afford food. The counter is that this would hit the poor and marginalised farmers as well as the poorest consumers of energy the most. Instead, cuts should be made elsewhere such as defence and pensions.

Similarly, a key factor while choosing the allocation should be whether the money spent maximises job creation. India has been suffering from massive open unemployment and several experts argue that instead of giving tax breaks to the big companies, the government should bolster India’s micro and small enterprises and urgently invest in boosting their skill set.

What should the government do on February 1? What are your expectations from the Union Budget 2023? Share your views and queries at udit.misra@expressindia.com

Until next week,

Udit

[ad_2]

Source link